|

|

| Feedback |

|---|

Real Resources Review: A little makes a lot?I sent John Busby's 7th August article to a friend who understands more about nuclear power than I do. His reaction was that 'Mr Busby is not conversant with the concept of pebble bed reactors'. I would like to ask Mr Busby how he views that technology and whether he would care to tackle it in an article for the uninitiated like myself? Kind regards, Paddy Imhof

The problem is that mining of uranium is running down, whatever form of reactor is envisaged. See Die Welt which reports the imminent closure of some of the French reactors due to fuel shortages. The thorium alternative and fast breeders are dependent on vast development programmes which with the rapid and progressive failure of the nuclear industry will never be funded. As far as the pebble bed reactor is concerned it depends on the integrity of the pebbles and as these contain graphite this is likely to lead to the demise of this technology. The seven UK AGR's are likely to close prematurely as the graphite moderator blocks are disintegrating due to the irradiation which causes structural breakdown. Also there is an overheating due to the Wigner Energy effect which leaves a residual heat in the graphite. The gas-cooled fast reactor is also an unlikely candidate for funding for this reason as it relies on graphite moderation. The nuclear lobby in desperation is arguing that uranium can be extracted from the earth's crust and seawater and looks to fast breeders to generate ever more plutonium. All of which is fantasy. We do not have to wait too long for some of the

lights to go out in France, which will hopefully lead to a reality

check! |

| Shop until the planet drops |  |

|

| By Jon Rynn | |||

| May/04/2007 | |||

|

By compartmentalizing political, economic, and even ecological theory, the fate of the planet is being jeopardized. By concentrating on just politics, a political theorist does not consider the importance of being a good steward for the economy and ecosystems. The discussion of political democracy is impoverished, because it should be clear by now that excessive concentration of economic power leads to a thoroughly warped democratic political system. As one example, the film An Inconvenient Truth has

allegedly led to a “tipping point” in public consciousness about

global climate change (“Tipping Point” having been a best-selling

book). Convince people to buy compact fluorescent light bulbs.[1]

Accountants of the world, unite!At a more serious level of problem-solving, we have the spectacle of many different percentage-based solutions, typified by the Kyoto Protocol treaty. The idea is that numbers will somehow fire the public’s imagination to drastically change…well, what is to be changed is exactly what is not discussed. For instance, to pick on one proposal among many, it is advocated that we should cut carbon emissions by “20% by 2020”. Catchy, no? Well, according to a management guru I heard being interviewed on radio, actually, no.[3] People understand ideas and think most clearly when they can imagine a particular scenario, when they can actually picture the alternative, not when a political program that only an accountant could love is unfurled as a revolution in the making. Global climate change solutions are just the beginning of what we are going to have to confront early and often. The most pressing global environmental issue right now is the mass extinction and wholesale destruction of ecosystems that is proceeding apace, not rising temperatures. In fact, some scientists are talking about convening an IPCC-type body to try and make these problems front and center.[4] One can be sure that shopping solutions will be proposed as an antidote here as well. Those concerned about the phenomenon of peak oil, or at the very least the end of the era of cheap oil, are busy just trying to get the issue into public discussion, but the same dilemma presents itself: in order to move our civilization off the path of fossil fuels and the wholesale destruction of ecosystems world-wide, governments at all levels, and not the market, will have to take the lead, and will have to use massive resources to do it. All the shopping in the world is not going to do it, and neither will targets such as a 2% reduction per year. An incremental approach won’t work. Because of the nature of the problems, some leaps will have to be made, and the market cannot make leaps.

Such a program might very well result in more fossil-fuel use for ten years, not less, but at the end of those ten-years, we might see a huge decrease in fossil-fuel use, say 50% for the sake of argument, with large decreases for years to come. By contrast, a program of small decreases in fossil-fuel use per year could only be done by incremental changes, such as increasing fuel efficiency in cars, which has a limit, or trying carbon capture for coal plants, which may not be possible, or legislating energy efficiency, which may be nullified by continued growth. By ignoring government programs as a source of solutions, not only does a realistic solution becomes virtually impossible, it becomes very difficult to paint a clear picture of what a solution will look like. The importance of being liberal

The sad story of the idea of governmental intervention in the

economy is partly to blame for our quandary. Since the reigns of

Reagan and Thatcher, the dominant worldview of conservatives (and

even liberals) has been that government is incapable of doing

anything positive about the economy. One of Reagan’s typically cruel

jokes was that “The most dangerous words in the English language

are, ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help’”. The implicit

ideology of the Bush Administration seems to be “The government

ain’t comin’ and there’s no one to help”. Ironically, this attitude

is a variant of what was originally called liberal thought, which

challenged the legitimacy of tyrannical government. To make matters worse, as James Howard Kunstler points out in The Geography of Nowhere, Americans have a very long history of using land very individualistically, without regard for public space, summed up in the phrase, “Nobody’s going to tell me what to do with my land!” Into this ideological vacuum concerning the proper role of government in the economy came the ideas of

Friedrich List and Alexander Hamilton were concerned with the

swamping of national markets by the British, and proposed high

protective tariffs as a solution to the problem. Such a system

actually worked quite well, at least into the 1920s, but the problem

today is that many on the Left seem to think that trade is the main

battlefield on which the forces of government can be used to create

a just economy. Free market capitalists, calling for free trade, were the progenitors of today’s conservatives, arguing that economic theory shows that the less government interference the better the economy will be. Communist theory, which was really a seat-of-the-pants set of economic principles developed in the 1920s, went to the opposite extreme and proposed that production over the entire society be planned by the government. This was really a nonsolution to the problem of governmental-intervention into an economy, because the real goal of a centrally-planned economy is to give priority to the military-industrial complex (the “commanding heights”, in Lenin’s phrase).[6]

The track record of actually-existing governmental intervention is quite good, but has had no overarching theory to justify it. Discussions of interventionist policies tend to seem ad-hoc and country-specific. For instance, Japan famously used “administrative guidance” of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), to steer the country to its preeminent manufacturing position after WWII. The Europeans, in various ways, used their governments to rebuild after the utter destruction of World War II and to catch up with the United States. Before World War II, even the U.S. government intervened at certain critical points, and after World War II the Federal government played a crucial role in suburbanizing the continent.[7] Thinking outside the boxesBy compartmentalizing political, economic, and even ecological theory, the fate of the planet is being jeopardized. By concentrating on just politics, a political theorist does not consider the importance of being a good steward for the economy and ecosystems. The discussion of political democracy is impoverished, because it should be clear by now that excessive concentration of economic power leads to a thoroughly warped democratic political system.

On the other side, the great tragedy of Marxist thought has been its refusal to understand the importance of either political or economic democracy. Capitalism as a system cannot receive all the blame for ecological destruction when the dictatorships of the Soviet state and its clients were even worse guardians of the environment than the capitalist countries, their records as worst environmentalists of all-time being threatened by the current Chinese regime.

Location, location, locationPerhaps a good place to start in constructing a better combination of political, economic, and ecological theory would be to first define what political and economic systems are. Economics is often defined as the allocation of scarce goods, but such a definition does not take production into consideration. If we instead define a production system as the transformation of matter and energy into goods and services, and the distribution system as the allocation of those goods and services, then and economic system can be defined in terms of both production and distribution.[8]

The state’s greatest spatial intervention into any economy is the way it allocates land. Since the state controls most of the means of coercion within a territory, then it can effectively do whatever it wants with the land and the buildings and infrastructure on that land (in the U.S. this is acknowledged in the idea of eminent domain). For instance, by using zoning laws, the state and local governments in the United States created suburban areas that are devoid of stores or workplaces, necessitating the use of the automobile. On the other hand, the fact that in the Soviet Union all land and buildings were the property of the state meant that when the Russian economy collapsed in the 1990s at least people had a place to live because the government wasn’t about to throw everyone into the street.[9]

In the United States, the transportation system, although public, was constructed for the benefit of the oil, car, tire, and road-building industries. The electrical systems, although more rationally controlled by various levels of government, have been turned into money machines for private utilities, orienting the energy infrastructure towards less-efficient gigantism and centralization. Even in the oil industry, most of the remaining global reserves are owned by national oil companies, while the U.S. and Britain are stuck with century-old oil companies that use their massive profits for their own ends. Unlike the U.S., the phone and cable systems in many European countries are government-owned because communication systems are a natural monopoly. Local and national governments are the logical place to put ownership and control of much of the economy and environment. Finding solutions that fit the problemsWe are collectively, globally, now confronted with a situation in which political/economic/ecological business as usual will lead to catastrophe. We inhabit a civilization that is going in the wrong direction fast: based on fast-diminishing fossil fuels that will require more and more resources for their exploitation and distribution; a global free-for-all for the overexploitation and destruction of the forests and oceans; a global agricultural system that is also destroying itself ecologically as well as dependent on fossil fuels; and in the middle of the global economy sits a country, the United States, busy tearing up the roots of its wealth, its manufacturing system. And shopping is supposed to solve all of these problems.

Many people have noted that during World War II, or during the space program in the 1960s, “we” accomplished great goals. But “we” didn’t do it through shopping, “we” did it with the best, if very imperfect, way that has been devised by humanity to engage in collective action, a democratically-elected government. If companies were employee-owned and controlled, chances are that a new national and even global effort to restructure the planet would be more just and fair. If towns and cities controlled their own transportation, energy, water, and communications systems, and mandated that manufactured goods for those systems be produced nationally or locally, so much the better. But however the political economy of a nation is structured, governments are going to have to do the heavy lifting. The same shopping-until-you’re-dropping attitudes affect the U.S. manufacturing sector. As U.S. manufacturing started its massive decline, the response was to implore us to “Buy American”. In my next article, I will explore the consequences of suburbanism on the U.S. economy. Jon Rynn will relaunch his blog the week of May 7th, at jonrynn.blogspot.com. You can also find old blog entries and longer articles at economicreconstruction.com. Please feel free to reach him at This email address is being protected from spam bots, you need Javascript enabled to view it and jonrynn.blogspot.com

[2] I visited the following web sites: Sierra club, Environmental Defense Fund, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) , Greenpeace, Union of Concerned Scientists, and Conservation International. At a very sophisticated level of analysis, Greenpeace in their “Energy [r]evolution” document, still rely on fiddling with market mechanisms. For buying carbon “offsets”, see “Carbon neutral is hip, but is it green?”, New YorkTimes, 4/29/2007, by Andrew Revkin. [3] See http://www.madetostick.com/thebook/ [4] See Julia Whitty, “Gone”, Mother Jones, May/June 2007 [5] I further elaborate on such a plan in my article in “Taking the Long View”, “How to create an efficient fossil-fuel-free economy”. One trillion dollars is a ballpark figure for the revenue obtained by drastically curtailing the U.S. Defense department and restoring the tax code for the wealthy and corporations to pre-Reagan levels. No problem! For a proposal to replace all electricity generation with wind, see Gar Lipow’s blog at gristmill.org. For a rail proposal, see the following link. The German and Japanese governments have started to directly fund putting solar panels on buildings. [6] I made the case for this statement in my article in “Is the sun setting on the U.S. military empire?”, Taking the Long View. [7] For Japan, the classic work is Chalmers Johnson’s book MITI and the Japanese Miracle, 1982; for Europe, Andrew Shonfield’s Modern Capitalism, 1966, and for the suburbanization of the U.S., see Robert Beauregard’s When America Became Suburban, 2006. [8] I elaborate on a definition of an economic system in my article “The Economy is an Ecosystem”, Taking the Long View. [9] See Dmitri Orlov’s “The U.S.S.R. was better prepared for peak oil than the U.S.”. | |||

|

| Register Free to receive updates of latest stories |

|---|

| Polls |

|---|

A specter

is haunting the world, but it is not a well-defined ideology, like

capitalism or communism. And yet, since World War II, it has been

responsible for more destruction than these ideologies, creating a

civilization that is copied the world over, one that specializes in

using up as much oil and coal, forests and land as possible. It is

the specter of suburbanism, the idea that it is everybody’s

God-given right to live as far away from work, shopping, recreation

and friends and relatives as one wants to. Now that we are

confronted with a virtually intractable set of global problems, what

is the recommended path to global safety that seems to emanate from

this “non-negotiable lifestyle”? Shopping, of course!

A specter

is haunting the world, but it is not a well-defined ideology, like

capitalism or communism. And yet, since World War II, it has been

responsible for more destruction than these ideologies, creating a

civilization that is copied the world over, one that specializes in

using up as much oil and coal, forests and land as possible. It is

the specter of suburbanism, the idea that it is everybody’s

God-given right to live as far away from work, shopping, recreation

and friends and relatives as one wants to. Now that we are

confronted with a virtually intractable set of global problems, what

is the recommended path to global safety that seems to emanate from

this “non-negotiable lifestyle”? Shopping, of course! We learn in the movie that

hundreds of millions of people may have to flee for higher ground

from swelling seas, other hundreds of millions may be displaced by

drought and famine, whole communities may be wrecked and untold

species eliminated. And what is the goal of the organization that

the producer of the movie has established?

We learn in the movie that

hundreds of millions of people may have to flee for higher ground

from swelling seas, other hundreds of millions may be displaced by

drought and famine, whole communities may be wrecked and untold

species eliminated. And what is the goal of the organization that

the producer of the movie has established? Other

advice, coming from many quarters, is to buy a more fuel-efficient

car, such as a Toyota Prius. One should also buy reusable shopping

bags, energy-efficient appliances, tune up your car at prudent

intervals, maybe buy carbon offsets so that somehow your

coal-generated electricity is balanced by planting a tree, and any

number of other creative ways to spend your money, many provided by

our leading environmental organizations.

Other

advice, coming from many quarters, is to buy a more fuel-efficient

car, such as a Toyota Prius. One should also buy reusable shopping

bags, energy-efficient appliances, tune up your car at prudent

intervals, maybe buy carbon offsets so that somehow your

coal-generated electricity is balanced by planting a tree, and any

number of other creative ways to spend your money, many provided by

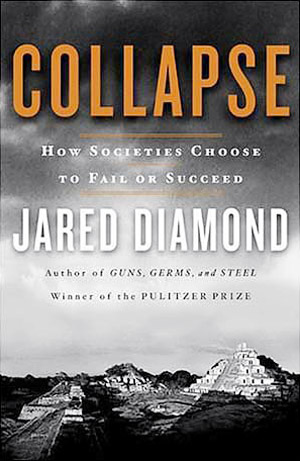

our leading environmental organizations. As Jared

Diamond notes in his book “Collapse”, one of the features of the

inability to prevent catastrophe is the refusal to change cultural

ideals. How did we get to the point where the culture has paralyzed

itself by refusing to use the government for necessary projects?

As Jared

Diamond notes in his book “Collapse”, one of the features of the

inability to prevent catastrophe is the refusal to change cultural

ideals. How did we get to the point where the culture has paralyzed

itself by refusing to use the government for necessary projects? John

Locke and others concentrated their writings on how governments

should behave in the political sphere, and this attitude quite

easily moved over the economic sphere: “keep the government out of

my business” (or “off our backs” to use Reagan’s formulation).

John

Locke and others concentrated their writings on how governments

should behave in the political sphere, and this attitude quite

easily moved over the economic sphere: “keep the government out of

my business” (or “off our backs” to use Reagan’s formulation). They seem

to have forgotten that government can be used as a positive force in

the economy, even beyond providing a social safety net and

regulation of goods and services.

They seem

to have forgotten that government can be used as a positive force in

the economy, even beyond providing a social safety net and

regulation of goods and services.

By

allowing neoclassical economists to control economic discourse, the

government is seen as only capable of sullying the purity of the

free market. Economists have had a tendency to turn a blind eye to

dictatorship; as long as the dictator doesn’t interfere in the

economy, there are allegedly no ill economic effects. During the

Cold War, the struggle between America and the USSR was often posed,

not as a struggle between democracy and dictatorship, but as a

struggle between the free market and central planning.

By

allowing neoclassical economists to control economic discourse, the

government is seen as only capable of sullying the purity of the

free market. Economists have had a tendency to turn a blind eye to

dictatorship; as long as the dictator doesn’t interfere in the

economy, there are allegedly no ill economic effects. During the

Cold War, the struggle between America and the USSR was often posed,

not as a struggle between democracy and dictatorship, but as a

struggle between the free market and central planning. By

looking at ecosystems as separate from humanity, environmentalists

seem incapable of envisioning the necessary political and economic

changes that must be made to solve the roots of the current

ecological crises. Democratic regimes have a better environmental

track record than dictatorial ones, and in addition, arguments can

be made that economic democracy is a precondition for an

environmentally benign society. By not proposing an alternative to

free market governmental policies, environmentalists are left with

the proposition that we can have better global living through better

shopping.

By

looking at ecosystems as separate from humanity, environmentalists

seem incapable of envisioning the necessary political and economic

changes that must be made to solve the roots of the current

ecological crises. Democratic regimes have a better environmental

track record than dictatorial ones, and in addition, arguments can

be made that economic democracy is a precondition for an

environmentally benign society. By not proposing an alternative to

free market governmental policies, environmentalists are left with

the proposition that we can have better global living through better

shopping. In

attempting to define a political system, some theorists have focused

on how a political system, stripped to its essentials, constitutes

the social control of space. For instance, the political sociologist

Max Weber defined the state as that organization that controls the

legitimate means of violence over a certain territory. Some of the

most important acts of a state are those that involve peoples’

position within its territory: prisons ensure that a law-breaker

stays in a particular spot, execution or expulsion eliminates that

person from the territory, rules governing how people can go into or

out of a country are among the most bitterly divisive, as we see now

in immigration debates; and border disputes can be the most

passionate and bloody that states engage in.

In

attempting to define a political system, some theorists have focused

on how a political system, stripped to its essentials, constitutes

the social control of space. For instance, the political sociologist

Max Weber defined the state as that organization that controls the

legitimate means of violence over a certain territory. Some of the

most important acts of a state are those that involve peoples’

position within its territory: prisons ensure that a law-breaker

stays in a particular spot, execution or expulsion eliminates that

person from the territory, rules governing how people can go into or

out of a country are among the most bitterly divisive, as we see now

in immigration debates; and border disputes can be the most

passionate and bloody that states engage in. Governments

at all levels therefore have the responsibility to structure

the use of land so that the economy and the ecosystems that the

economy depends on can thrive. Since particularly in industrial

societies the use of land is dependent on large-scale

transportation, energy, water, and communications systems, the

government is critically involved in the design of infrastructure,

no matter what the ideology. Surburbia could never have happened had

the government not intervened forcefully, through means such as

mortgage insurance and tax write-offs and the construction of the

Interstate Highway System. Free market ideology did not get in the

way of those policies, because people understand, if only vaguely,

that governments are absolutely necessary -- even to maintain their

“non-negotiable” way of life.

Governments

at all levels therefore have the responsibility to structure

the use of land so that the economy and the ecosystems that the

economy depends on can thrive. Since particularly in industrial

societies the use of land is dependent on large-scale

transportation, energy, water, and communications systems, the

government is critically involved in the design of infrastructure,

no matter what the ideology. Surburbia could never have happened had

the government not intervened forcefully, through means such as

mortgage insurance and tax write-offs and the construction of the

Interstate Highway System. Free market ideology did not get in the

way of those policies, because people understand, if only vaguely,

that governments are absolutely necessary -- even to maintain their

“non-negotiable” way of life. Can shopping build a

widespread, comfortable rail system? Jump start a solar/wind energy

system even if renewable energy is marginally more expensive than

coal? Rebuild town and city centers so that people can walk instead

of drive? Create ocean and forest preserves that are adequately

policed, worldwide, so that we can avoid a human-induced mass

extinction? Make the switch from the current industrial agricultural

system, which has been fundamentally shaped by the Federal

government since the 1920s in any case, to a local,

permaculture-type system, without massive disruptions?

Can shopping build a

widespread, comfortable rail system? Jump start a solar/wind energy

system even if renewable energy is marginally more expensive than

coal? Rebuild town and city centers so that people can walk instead

of drive? Create ocean and forest preserves that are adequately

policed, worldwide, so that we can avoid a human-induced mass

extinction? Make the switch from the current industrial agricultural

system, which has been fundamentally shaped by the Federal

government since the 1920s in any case, to a local,

permaculture-type system, without massive disruptions?